READING MUSIC 4

By Mary Jane Gormley

Note: this is the last in a series of four educational articles on the basics of reading music, intervals and notation. These building blocks were originally presented as a workshop for harmonica players, but they are a valuable guide for anyone wanting to learn to read music. The print-ready PDF of this article can be downloaded here.

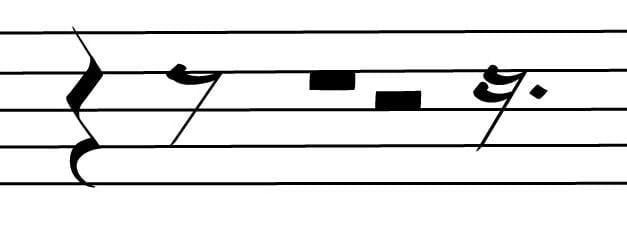

A pair of eighth notes adding up to a quarter-note count in the music are often barred together, as here. We have 3/4 time, and here the first two notes together come in on the third count of the measure: one two three and.

A pair of eighth notes adding up to a quarter-note count in the music are often barred together, as here. We have 3/4 time, and here the first two notes together come in on the third count of the measure: one two three and. This piece has almost every possible combination of notes to add up to three counts— eighths, quarters, halves, and even a couple of sixteenth notes. Count the one-two-three time out loud (with ands if you wish) and clap the notes; it’s involved, but you’re getting good at this.

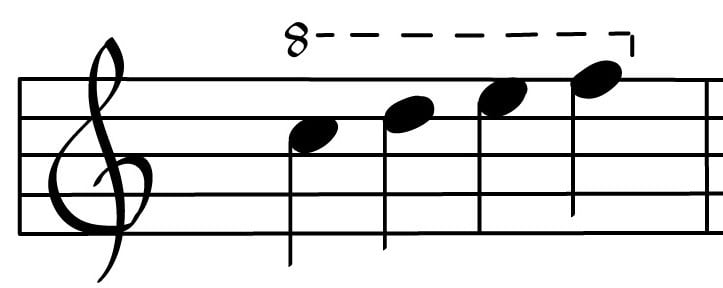

Then the intervals! Same, third-up, third down . . . some bigger, and one we haven’t met before, the octave (eighth). Start on blow five.

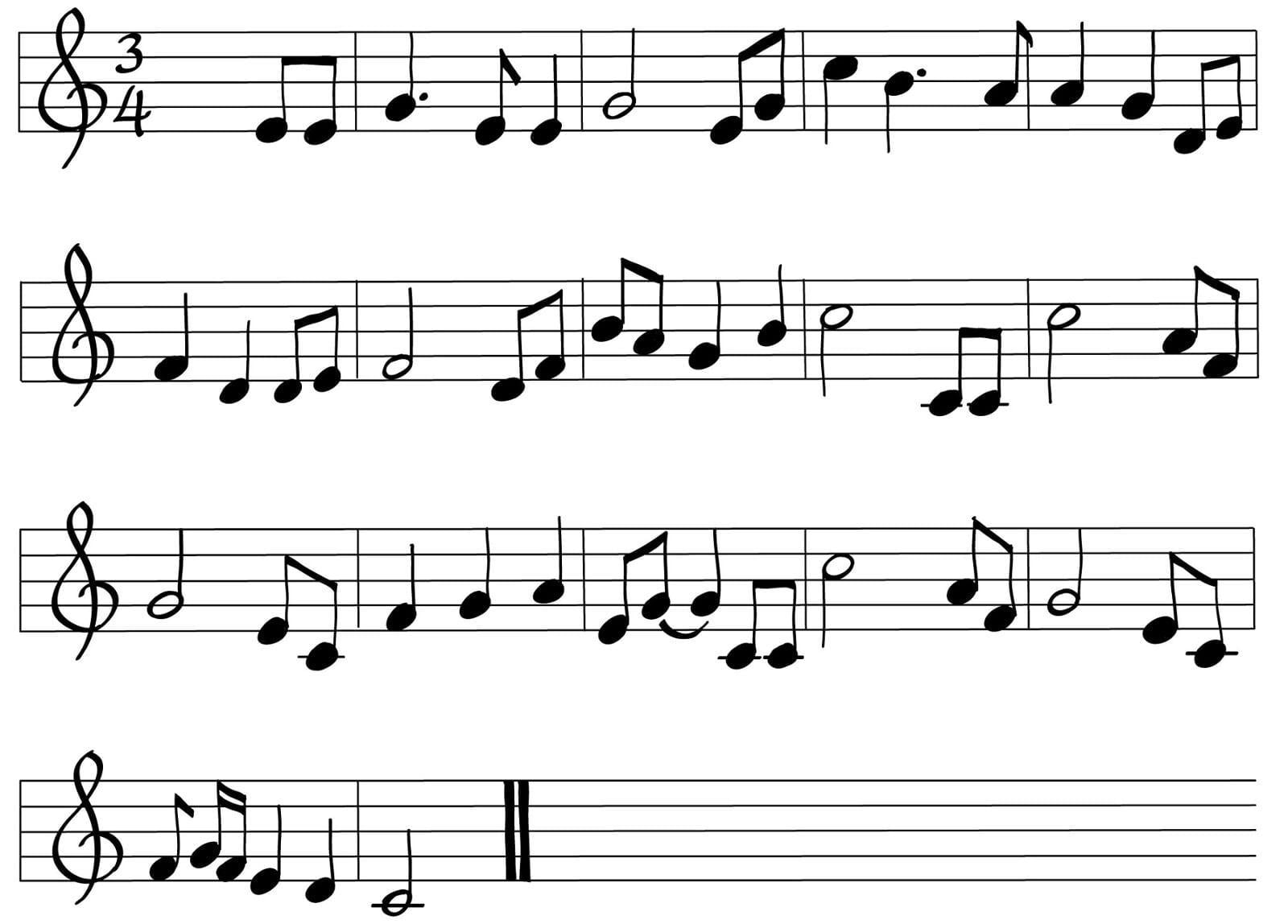

Clefs: The G clef is very often bracketed with the lower F clef, especially for pianos and four-part vocals. The do-re-mi is a pattern of notes we are all familiar with; in this illustration, the bottom note on the G clef (do) and the top note on the F clef (also do) are the same, middle C. In do-re-mi, the intervals between the notes are not all the same! Mi–fa and ti–do are half tones apart, while all the rest of the intervals are whole tones—hence the term diatonic scale, whole and half tones (here it has nothing to do with harmonicas).

Clefs: The G clef is very often bracketed with the lower F clef, especially for pianos and four-part vocals. The do-re-mi is a pattern of notes we are all familiar with; in this illustration, the bottom note on the G clef (do) and the top note on the F clef (also do) are the same, middle C. In do-re-mi, the intervals between the notes are not all the same! Mi–fa and ti–do are half tones apart, while all the rest of the intervals are whole tones—hence the term diatonic scale, whole and half tones (here it has nothing to do with harmonicas). The line and space notes have letter names, shown at the ends of the staff lines above.

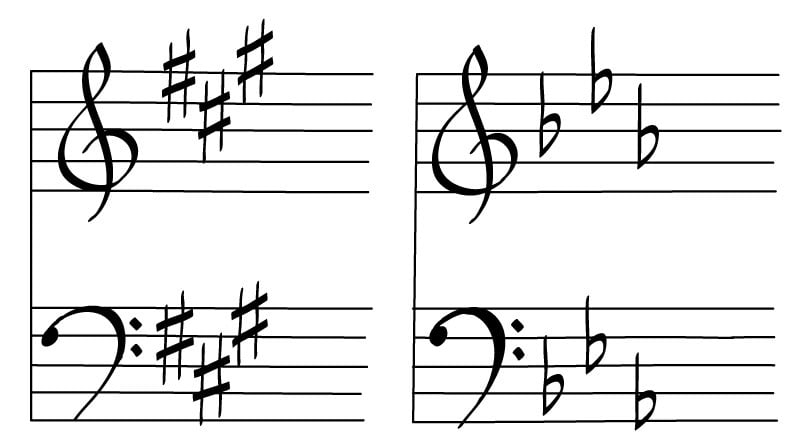

To sing or play a familiar tune starting on a higher or lower note, we need to adjust the intervals—and that’s where sharps and flats (the black notes on a keyboard) come in. A sharp raises a note by a half tone, and a flat lowers it. In the key signature, which appears at the beginning of every line of music, each sharp and flat is shown once, but it applies to all the notes of that name throughout the piece—the first sharp here is an F sharp; the first flat is a B flat.

There may be an occasional note variation in the middle of a piece; those are called accidentals, and each one applies only to the measure in which it is written—it ends at the bar line. We have here sharp, flat, natural (cancels any existing sharps or flats for that note); and double sharp, double flat, and natural again. Music writers often reinstate the original sharps or flats in the next measure.

Music writing isn’t entirely as organized and predictable as I have made it here. In fact, there’s a great deal of flexibility in it. The chief reference work is Gardner Read’s Music Notation; it’s over 450 pages, and nobody knows it all. I hope these four short lessons have given you a start.

♪MJNG